Beleidscyclus

In search for an enforcement strategy for the Common European Asylum System

By Salvatore Nicolosi

The reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) is one of the major regulatory challenges to the European Union (EU), which has continuously attracted academic attention (Nicolosi, 2019). Less consideration has been given to the dynamics of enforcement of that policy. Yet, this is a crucial issue, as acknowledged by the European Commission, the migratory pressure of the most recent years stressed the ‘structural weaknesses and shortcomings in the design and implementation of European asylum and migration policy.’ Apart from a ‘protracted implementation deficit,’ EU asylum law has been suffering from a ‘protracted compliance deficit’ (Thym, 2017). This makes the need for a more effective enforcement strategy all the more urgent. This post, therefore, aims to explain whether EU direct enforcement mechanisms can be more effective than traditional forms of enforcement by State authorities.

Conceptualising Enforcement in EU Asylum Law

Different definitions of enforcement exist in literature. Broadly it ‘comprises preventive and repressive monitoring, investigating and sanctioning substantive norms’ (Vervaele, 1999). In this connection enforcement is, therefore, dependent on the implementation of the substantive rules of a given policy. The EU has been traditionally seen as a regulatory authority (Majone, 1994), while the power of enforcement is left in principle to the Member States (Cremona, 2012). This contributes to explain why studies on enforcement at the European level generally focus on domestic transposition of EU law rules (Scholten, 2017). The CEAS seems to perfectly illustrate such a paradigm which is common to many areas of EU law. It has gone through different phases of European regulation and the practice has flagged the tensions determined by its enforcement at the State level. In EU asylum law, in fact, problems of enforcement are a direct consequence of non-implementation or wrong implementation of EU rules. This can occur for different reasons, such as the lack of resources to apply EU rules (Thym, 2017), as significantly epitomized by the Court of Justice with reference to the ‘systemic deficiency in the asylum procedure and in the reception conditions of asylum seekers’ in Greece. In addition, the predominant regulatory paradigm of minimum harmonization has proved detrimental to the practical effectiveness of the CEAS, because of the wide margin of discretion left to the Member States (Vicini, 2020).

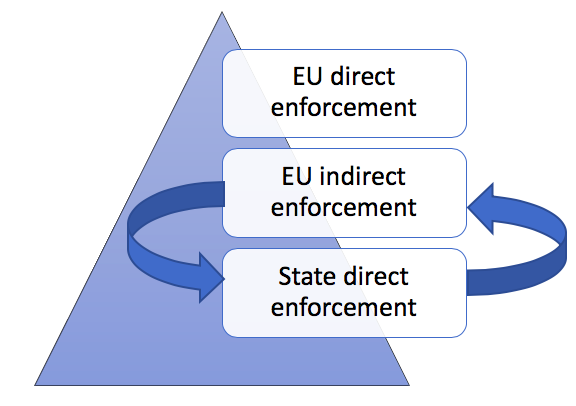

Another more problematic reason is the lack of political will, as illustrated by the arm wrestling on the relocation of asylum seekers between the Visegrad States and the EU, culminating in the recent CJEU’s ruling. This confirms how direct enforcement through state authorities is usually complemented by forms of indirect enforcement by different organs of the EU administration involved in the supervision of the application of the law by state authorities (Rowe 2009: 189). The EU has also ‘acquired enforcement competences in areas where it previously only had regulatory authority’ (Scholten & Scholten, 2017) with a significant expansion of direct enforcement powers. This process has determined what the doctrine defines as ‘Europeanization’ or ‘verticalisation of enforcement’ (Scholten, 2017), which is becoming progressively relevant also in the field of asylum.

A typology of enforcement strategies in EU Asylum law

The heterogenous nature of EU law enforcement suggests that a mix of tools is necessary to address the specific problems of enforcement in the CEAS. This needs actions both at the State and EU levels, where forms of direct enforcement can be more effective than traditional means of indirect enforcement such as infringement procedures.

a) Direct enforcement by State authorities

Direct enforcement by State authorities is necessary to ensure an effective policy because, as highlighted, enforcement is dependent on the implementation of the substantive rules. From this perspective, the EU legislative choices can be crucial: a legislation based on regulations can certainly ensure a stricter enforcement by Member States, that have, for instance, less discretion already at the level of implementation. However, ‘a regulation may be directly applicable, but its effectiveness continues to be dependent on administrative capacities and practices on the ground’ (Thym, 2017). The Dublin Regulation is a clear example of a regulation with very detailed prescriptions but a very low level of enforcement (Maiani, 2017).

b) Indirect enforcement by the European Commission

The difficulties in ensuring full compliance with EU rules by State authorities raise the question of the effectiveness of indirect enforcement by the European Commission. A number of infringement proceedings have been launched, and very recently – for example – the Court in FMS confirmed that Hungary’s legislation encroaches upon the Procedures Directive. Nonetheless, even after a successful action brought before the Court, this traditional enforcement mechanism proves ineffective, because Member States can repeatedly violate EU law, as illustrated by the relocation of asylum seekers with the judgment issued three years after the expiration of the Relocation Decision.

This cannot lead to the conclusion that infringement procedures have to be delayed or avoided, on the contrary they are necessary but not enough. They play a role in highlighting the axiological nature of EU law enforcement. This is meant to ensure the commitment of the EU and its Member States not only to adequately enforce the EU legislation but also to ensure the compliance with the values on which the Union is founded (De Schutter, 2017), and asylum legislation is indeed adopted to serve such values, first and foremost fundamental rights protection.

c) Direct enforcement by the EU

The limits of indirect enforcement coupled with the operational nature of the CEAS explains the growing trend to the verticalization of enforcement also in EU asylum law. This is clearly reflected by the expansion of the operational powers of the European Asylum Support Office (EASO) and its transformation into a more powerful Asylum Agency (Nicolosi & Fernandez-Rojo, 2020). The EASO’s increasing involvement in the refugee determination process in the Greek Hotspots confirms the need for Member States to integrate the EU support within their domestic system, while keeping the primary administrative responsibility for an asylum application. This form of EU direct enforcement has the potential to overcome the CEAS inherent problems.

The lack of national resources can be counterbalanced by the injection through the Agency of Asylum Support Teams that can provide expertise in applying EU rules. This comes also with a financial relief on the Member States concerned. Even the most difficult problem of the lack of political will could be potentially contrasted by empowering the agency with specific operational tasks that, especially in case of emergency, can be enforced against the will of the Member State (Thym, 2016). Lastly, even if the regulatory framework is based on Directives, the agency can assist Member States by monitoring the correct implementation of EU rules.

Concluding remarks

The relaunch of the CEAS reform through the upcoming new European Pact on Asylum and Migration offers the chance to reconsider a strategy for the enforcement of EU asylum law. This would require strategic legislative choices and a mix of enforcement tools. Traditional indirect enforcement mechanisms, such as infringement procedures, are not enough. On the contrary, EU direct enforcement through EU agencies (Scholten & Luchtman, 2017) has a great potential because of the teleological nature of the CEAS which is meant to ensure the harmonious application of the Refugee Convention throughout the EU. Naturally, this requires careful legal design and tighter coordination between the domestic systems and the agency, but it can constitute a major step forward for the enforcement of the CEAS.