Beleidscyclus

Why is “four” better than “three” when it comes to the lines of defence in financial institutions?

Certainly one of the greatest banking scandals of any age, the LIBOR fraud rocked the global financial industry. Manipulating interbank interest rates for almost two decades, the scale of the LIBOR deceit was staggering: 3 continents, 10 countries, 20 banks.

How could that happen on such a massive scale?

What LIBOR and other crises have shown is that banks need to enhance corporate governance measures. Most importantly, such incidents have led to a further prioritisation of governmental and supervisory agendas relating to the potential systemic implications of weak internal control systems, shifting the focus from the soundness of individual financial entities to the integrity and stability of the whole financial system. As Schwarcz maintains, the sheer perils financial supervisors have currently to cope with are attached to the risk “that a trigger event, such as an economic shock or institutional failure, causes a chain of bad economic consequences—sometimes referred to as a domino effect”. Systemic risk, indeed.

This calls for a greater prominence of macro-prudential policies relating to misconduct at banks, but also for closer cooperation between supervisors, and external and internal auditors so as to mutually contribute in identifying, evaluating and managing the risks that the increasing degree of integration and interconnectedness in the financial sector brought about (Report on misconduct risk).

Société Générale in 2008, UBS in 2011 and Banca Etruria in 2015 made it clear how far weak board-level procedural safeguards and systems of internal control can go. The Internal control framework is in fact conceived to “ensure effective and efficient operations, adequate control of risks, prudent conduct of business, reliability of financial and non-financial information reported, both internally and externally, and compliance with laws, regulations, supervisory requirements and the institution’s internal rules and decisions” (Guidelines on Internal Governance).

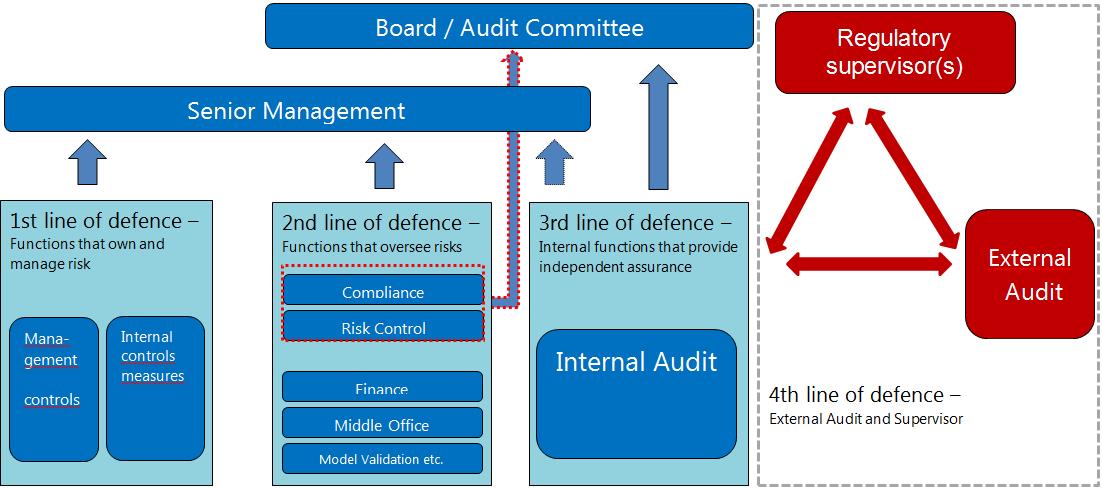

Up until now, the “three lines of defence model” has been used traditionally to model the interaction between corporate governance and internal control systems. At its simplest, and in accordance with the Institute of Internal Auditors’ view, the model is designed as follow:

The revenue-generating business units form the basis of the model and are referred to as the “first line of defence”. Depending on the type of industry in question, these units may include the production of physical goods or the provision of financial services such as trading, asset management, sales and client relationships.

The “second line” comprises various risk management and compliance functions (ie support functions) such as finance, compliance, risk control, model validation and back office, whose key duties are to monitor and report risk-related practices and information, and to oversee all types of compliance and financial controlling issues.

Finally, the “third line” encompasses the internal audit function, which provides independent assurance to senior management and the board on a broad range of objectives, including efficiency and effectiveness of operations, safeguarding of assets, reliability and integrity of reporting processes and compliance with laws and regulations.

The three-line of defence model has become the most common benchmark for assigning control and risk management responsibilities to business functions in an organisation. The original idea was to develop a model of general applicability for organisations. However, in “complex” corporate structures such as the ones governing financial institutions, the three-lines-of-defence model might prove to be unsuitable in dealing accurately with an organisation’s operational peculiarities which stem not only from the nature of the business itself but also from the specific institutional framework of the banking and insurance business (regulation and supervision) (See Coats on this subject). Hence, banks run a unique business in that they are intermediaries between savers and users of capital. Banking is considered to be a specific kind of activity resulting in high complexity, the involvement of many stakeholders and the existence of a high level of interlinkages amongst market participants (see De Haan and Vlahu, Mehran et all).

On a higher altitude, international standard setters and policy-makers are calling for a stronger interaction between banks and supervisors, particularly with respect to enhancing dialogue with the board and senior management on the governance of risk, including the development of an institution’s risk appetite framework and an assessment of its risk culture. In that respect, for instance, the Federal Reserve has recently addressed the issue and, building upon the 2003 Policy statement on the internal audit function, issued a new section entitled Enhanced internal audit practices. That section encourages examiners to “rely on the work performed by internal auditors” and to “supplement their examination procedures through continuous monitoring and an assessment of key elements of internal audit” (See Supplementary policy statement on the internal audit function and its outsourcing). The BCBS paper on the internal audit function in banks reaches similar conclusions when describing the relationship between internal audit and supervisors (The internal audit function in banks). It not only provides an overview of supervisory expectations relevant to the internal audit function (including quality assessment) but also explicitly underlines the benefits of enhanced communication between supervisors and internal audit functions.

Against this backdrop, the existing three-lines-of-defence doesn’t seem apt to reflect this need of further cooperation between “internal” and “external” controllers and, thus, to capture the peculiarities characterising regulated financial institutions and their organisational structure: a fourth line of defence may therefore exist by making supervisors and external auditors inherent part of the internal system of controls.

Embedding supervisors and external auditors’ role in the structure of the defence system could indeed mitigate the shortcomings of the traditional three-lines-of-defence model and increase the soundness and reliability of the risk management framework.

As the four-lines-of-defence model intends to enhance coordination between external parties and internal auditors, greater communication is at the basis of its success.

Communication works by reducing, if not eliminating, asymmetric information among the parties involved, provided, of course, that the treatment of information is such as to make risk control systems more effective. In some cases, imposing additional disclosure requirements may prove counterproductive if it causes the parties involved in the fourth layer to change their behaviour in an adverse way. This would aggravate the problem of moral hazard to the detriment of the effectiveness of the internal control systems. Increasing the amount of information is not good as such, and may even result in less effective and efficient control systems.

In that respect, the four-lines-of-defence model would entail a new setup of processes and rules, especially in terms of information that internal auditors, external auditors and supervisors are respectively required to share (or not allowed to share). These rules set forth the categories of information made available to whom, the procedures for obtaining documents and records, and the rules for limiting the release of exempt and confidential supervisory information and for protecting confidential information.

According to the four-lines-of-defence model, the external auditors might provide an autonomous assessment of the first three lines where this is relevant to the audit of the organisation’s financial reporting and to compliance with regulatory requirements. In this sense, by providing additional assurance to shareholders and senior management, external auditors, regulators and other external bodies have an important role to play in an organisation’s overall governance and control structure.

Moreover, the interaction between control functions (ie the internal audit function) and supervisors might result in an improvement to the tools and methods that could be used by supervisors in order to intensify their oversight of financial institutions, aiming at delivering pre-emptive, rather than reactive and outcome-based supervision. In other words, by virtue of improved communication channels with internal audit, supervisors might be provided with useful and reliable information to support their judgments and enable them to be more forward-looking in their assessments of risk. Better informed supervisors, armed with accurate information, help in ensuring that market stability is being maintained.

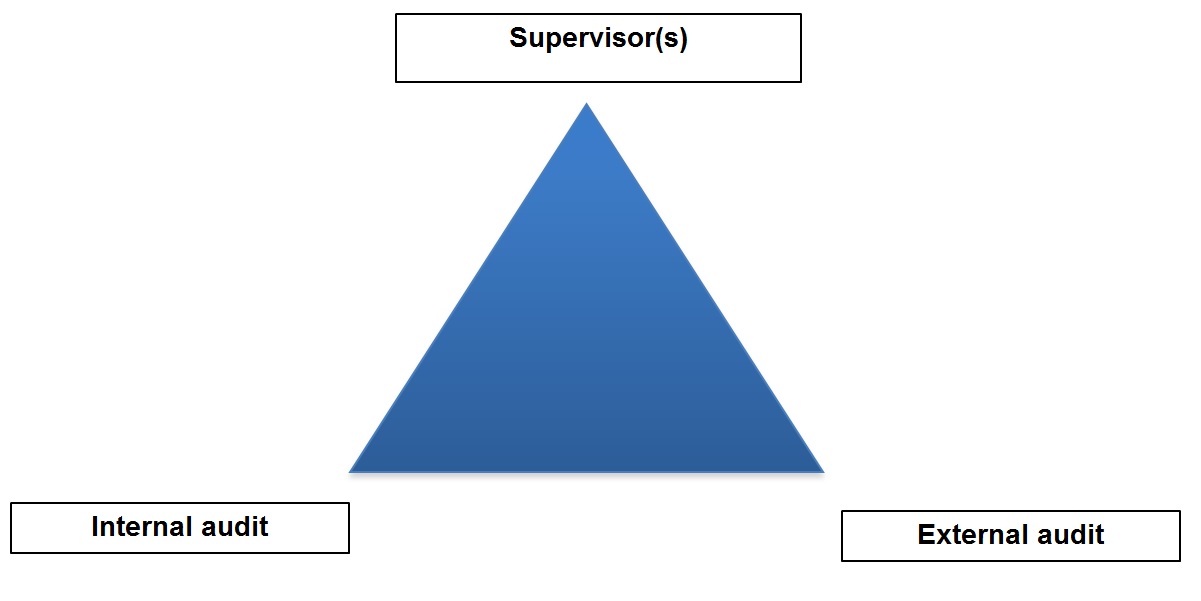

According to the four-lines-of defence model, the interaction between internal auditors, banking supervisors and external auditors could be depicted as a triangular relationship.

Building upon the concept of a “triangular”, new responsibilities and relationships between internal auditors, supervisors and external auditors come about. This might enhance control systems, but, if not structured and designed properly, problems of inadequate information flows could arise among those actors.

Specifically, the scope of information, the form of communication and the timing/frequency of communication are important elements in reinforcing the overall consistency of controls. By establishing and implementing a four-lines-of-defence model, the following features of the relationship should be mandated and effectively implemented:

- a) Regularity of information provided:

– definition of the terms and scope of the interaction; and

– exchange of information before and during the audit engagement, allowing flexibility (eg ad hoc meetings whenever necessary).

- b) Quality of interactions:

– ex post feedback on quality of interactions and information-sharing; and

– regular assessment of independence and objectivity of each party involved (eg the conditions of an external auditor’s appointment).

- c) Clear definition of authority and scope:

– Supervisors should have the power to request access to any type of information retained by external/internal audit;

– all three parties should jointly set the audit scope of the subject matter to be reviewed (eg joint discussion of financial statements); and

– all three parties should share their audit methodology and discuss critical action plans.

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) expressed great interest in this model, and it is going to provide some remarks and comments on its implementation. The conceptualisation of model opens up fruitful avenues for further research on the relationship between internal audit (third line of defence) and external audit and supervisors (both comprising the fourth line of defence). Despite their external status, in fact, the entities forming the fourth line of defence are active in supervising and monitoring control issues in the organisation, possibly increasing its resiliency also to systemic shocks.

This blog is based on a recent article written by Andrea Minto and Isabella Arndorfer for the Financial Stability Institute WP – Bank for International Settlements. For the full article, see http://www.bis.org/fsi/fsipapers11.pdf